Click Here for Printable Version

March proved to be a hugely complex month for markets with many cross-currents in play.

Dominating the news flow was the war in Ukraine. Initial fears of a wider European conflict, use of nuclear weapons and Europe’s gas supplies being cut off have, so far, proved to be unfounded.

The Ukrainians have put up a fierce resistance, helped by weapons and intelligence from the West.

Nevertheless, this is not over yet and may not for a long time yet. For the markets the big issue remains the gas supplies.

If Europe’s gas is cut off then Germany goes into instant recession. Is this likely? Not if Europe can pay and that is where the difficulty is. Sanctions have so far been very targeted, but with banks continuing to refuse or unable to handle gas payments in the roubles Russia is demanding, then the West’s carefully balanced strategy of helping the Ukrainians just enough whist still taking the gas might yet fall over.

Indeed, human rights issues may yet overrule economic ones. Furthermore, Russia hasn’t defaulted on its debts yet, but again physically paying interest is proving to be very difficult.

Just because the markets have started to move on from the war doesn’t mean that it has gone away.

Separate to the war, but of greater economic significance, is the dramatic fall in bond values globally and the ensuing rise in market interest rates. This time last year the US 10 year Treasury Bond interest rates were 0.5% they are now 2.5%.

Much has been made that this is due to inflation, it isn’t, this move is just the removal of the Covid stimulus packages, bond prices have simply gone back to pre-Covid levels.

If the global economy has moved to a new higher plane of growth (as it seems to have) then interest rates have further to rise.

The other major factor that the global economy has had to deal with is the resurgence of Covid in China. Their vaccines are not as protective as ours and the zero Covid policy has meant limited natural immunity.

Lock downs in Shenzhen and Shanghai will have a global economic impact, particularly on already stretched supply lines. The key barometer, in the very short term for all these various major market dislocations, is the price of Crude Oil.

Oil up, markets down and vice versa. Oil is also seen as the poster child for inflation and it is this that is central to market sentiment at present.

Economic Recap

The modern economic world only started in around 1980. Before that governments set interest rates, exchange rates and even wages through collective bargaining.

Moving money abroad was extremely difficult and investors could only buy shares in the UK, US, Holland, Canada, Hong Kong, South Africa and Australia.

In the space of 40 years the economic world has changed dramatically. With inflation rising globally the media is full of talk of “back to the ‘80s”, let’s hope not, as mortgage rates were 15%, but then again we did have MIRAS.

The Thatcher/Reagan years were essentially about the withdrawal of direct government involvement from the economy and removing support for allegedly “lame duck industries”.

Not only did businesses such as steel, shipbuilding, car manufacturing etc. see a loss of direct financial support they also couldn’t afford to borrow.

Interest rates were pushed to very high levels in order to choke off inflation. With borrowing rates way above the low levels of Return on Capital from mainly industrial businesses they ended up going bankrupt.

Why was inflation so high in the 1970s and 1980s, there are many conflicting theories.

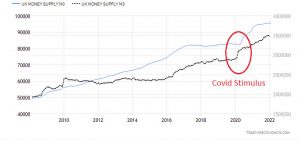

After 1980 the Monetary theorists took over the central banks and are still there. Here the belief is that increasing the money supply and doing it too quickly, leads to inflation. Control the supply of money, thus control inflation.

So in 1980s government spending was slashed and interest rates pushed up to reduce bank lending, increase savings and force capital to move from mature manufacturing to higher growth service businesses.

In recent years, with more sophisticated markets, this control of the money supply has also included forcing the banks to hold higher reserves (can’t lend as much) or changing lending criteria e.g. buy-to-lets or no 100% mortgages etc.

However, as the following chart shows the Covid stimulus has sent the Money Supply to the stratosphere.

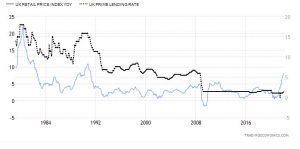

The first chart shows that if inflation and growth is returning to 1990-2008 levels then whilst we shouldn’t see 15% rates, might we in theory at least be seeing a return to the 5% level?

The key in the short term will be for the markets to work out whether this current high inflation is cyclical or structural?

Is it just the reopening pains post-Covid or has the transfer of so much hard cash from governments to individuals created a new higher level of spending that enables business to charge more in the face of shortages?

Generally there is not one simple answer, it is probably a combination of various structural and cyclical factors. The post Credit Crunch world of 2009 onwards was one where low interest rates and QE did not feed into the Money Supply, the banks simply hoarded the cash to rebuild their balance sheets and governments introduced austerity and higher taxes to pay off their debts.

Covid has changed the financial world. Governments are spending on the Green Industrial Revolution and wages are rising because so many workers have left the labour force. But we also need to remember that high inflation means higher growth and thus cheaper share prices.

Historic Investment Returns

The past 14 years since the 2008 Credit Crunch have been unusual with low economic growth and very little inflation, indeed many economies have flirted with deflation.

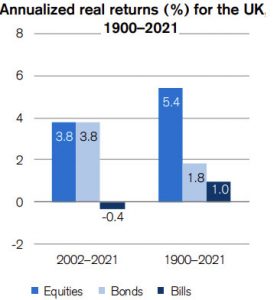

As this table shows investment returns have been unusual too. Including the crash, equity returns above inflation have been lower than the long term average and bond returns much higher. Also holding cash has diminished investors wealth.

Are we about to return to normal? The long term inflation average for the UK (including the 1970s and 80s) is 3.8% so it does feel like we might.

If we do then it is reasonable to assume that investment returns will do so too. Equity returns will go up and bond returns will go down.

Between 1990 and 2008 corporate profit growth in the S&P 500 averaged 8.1% p.a. between 2009 and 2020 it was 5.3%. This supports the theory that going forward equities are the best place to protect and grow wealth in a more inflationary world.

Source: Credit Suisse

Markets

We are currently in one of the most complex set of market circumstances we have seen in over thirty years of investing. The war in Ukraine has the potential to turn Germany’s gas off and trigger a European recession.

The longer this conflict goes on the more possible this is. Oil prices have surged, stimulating inflation that was already seeing price increases as post-lockdown consumer demand reached record levels. There are already implications from the gas price rise in Europe with many high gas users e.g. paper mills, shutting.

Furthermore, Covid has led to a reduction in the available workforce, thus adding wage pressures and skill shortages. But, will the huge and sad influx of Ukrainian refugees change this?

At the same time Covid has not gone away. Two of the biggest cities in China are back in lock-down, what will this do to the already disrupted supply of components?

In Europe Covid is again starting to have an impact, some countries with low vaccination rates are seeing hospitalisations rise.

On top of this we have the US Federal Reserve Bank raising interest rates back to pre-Covid levels. Some think they are moving too far, too fast and are risking recession. But mortgage rates on both sides of the Atlantic have decoupled from bond yields, so is this just a market obsession rather than a real world one?

The central banks and their respective governments thought that Covid would impact the global economy in a bigger way and for longer, they were wrong and far from protecting economies, they have perhaps inadvertently, through both money printing and government spending, kick-started a huge expansion in the money supply and thus an economic boom plus inflation.

Hence the scramble to unwind the stimulus asap. They might though get lucky, Covid is back and a possible European recession might just soak up enough of this excess money printing to bring inflation rapidly back down to the desired 2.5%-3% level.

Given all of this complex and potentially negative news flow it may be surprising that the equity stock markets are making upward progress? This is because companies like inflation, it is easier to make profits in an inflationary world.

History tells us that in the best place to protect your wealth in a such a world is the stock market. Bond yields and cash interest rates are lower than inflation whereas just equity dividend returns only are higher than bond yields and unlike bonds, will also increase each year by more than the rate of inflation.

Hence, JP Morgan estimates that a staggering $230bn moved from US Bonds to US equities at the end of March.

If you had invested $1,000 in the S&P 500 at the beginning of 1980 by the end of 1990 (including the 1987 crash) it would have been worth (with dividends) $4,605 a 14.9% p.a. return, comfortably beating inflation.

So whilst the media is painting a return to the 1980s as a bad thing, for the markets it was a very good period.

April 2022

Click Here for Printable Version

This information is not intended to be personal financial advice and is for general information only. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results.